| En noviembre de 2020, un grupo de presos políticos saharauis al que se hace referencia como el grupo Gdeim Izik, habrá pasado 10 años en cárceles marroquíes. Anticipándose al próximo trágico aniversario, WSRW pide la liberación inmediata e incondicional de estos presos políticos. En la madrugada del 8 de noviembre de 2010, una semana antes de que estallara la primavera árabe, el ejército y la policía marroquíes derribaron brutalmente un campamento de protesta pacífica, donde más de 10.000 saharauis se habían reunido en protesta por su exclusión socioeconómica en su propia tierra natal. está bajo ocupación marroquí. La ubicación del campamento fue en un sitio llamado Gdeim Izik, una zona desértica en las afueras de la ciudad capital, El Aaiún. Cuando el campamento fue quemado hasta los cimientos, estallaron peleas entre la policía y los saharauis frustrados. Tanto agentes de policía como civiles saharauis murieron durante los enfrentamientos. Un grupo de 25 hombres fue arrestado por su supuesta participación en la organización del campamento de protesta. Después de dos años y medio de detención arbitraria, fueron condenados en febrero de 2013 en un tribunal militar marroquí, la mayoría a condenas de entre 20 años y cadena perpetua. Entre los detenidos se encontraban destacados defensores de los derechos humanos del Sáhara Occidental. Uno de ellos es el secretario general de un grupo saharaui que monitorea la participación extranjera en el saqueo ilegal del territorio por parte de Marruecos. La principal prueba criminal utilizada en su contra consistió en confesiones, firmadas bajo tortura. El veredicto dictado fue apelado ante el Tribunal de Casación de Marruecos, que sostuvo que el tribunal no podía condenar a este grupo de activistas únicamente sobre la base de confesiones. Por lo tanto, cuatro años después, en 2017, el caso se volvió a juzgar ante un tribunal civil, se confirmó la mayoría de las sentencias y se reutilizaron las confesiones firmadas bajo tortura como principal prueba penal. Por lo tanto, el caso fue nuevamente apelado ante el Tribunal de Casación de Marruecos, que aún no ha dictado sentencia. Hoy, 19 de los 25 siguen en prisión. Su juicio fue una parodia de la justicia. La única prueba contra los hombres fueron las confesiones hechas bajo tortura. Aquí hay un informesobre el juicio kafkiano contra el grupo. El informe analiza las pruebas y los argumentos utilizados por el tribunal. “La violación del derecho internacional sobre el derecho a un juicio justo en la Declaración Universal de Derechos Humanos y de las demás obligaciones internacionales de Marruecos hace que la privación de libertad de los 19 detenidos sea arbitraria. Los 19 detenidos fueron sometidos a secuestros o detenciones que implicaron torturas o tratos o penas crueles, inhumanos o degradantes. Su trato ilegal ha continuado durante su detención. El grupo lleva detenido unos siete años. Su condena no se basó en suficientes pruebas materiales delictivas ”, afirmó Mads Andenæs, exjefe del Comité de la ONU sobre Detenciones Arbitrarias, en el prólogo del informe anterior. “Estos hombres no han hecho más que defender pacíficamente sus derechos humanos básicos. Han pasado 10 años de sus vidas encarcelados en base a juicios que no siguieron los estándares internacionales más básicos. Hacemos un llamado a la comunidad internacional para que presione a Marruecos para su liberación inmediata e incondicional «, dice Sylvia Valentin, presidenta de Western Sahara Resource Watch. La detención arbitraria de los prisioneros de Gdeim Izik fue tratada, entre otras cosas, en una comunicación emitida por los Procedimientos Especiales de las Naciones Unidas el 20 de julio de 2017 (AL 3 de marzo de 2017), firmada por el Grupo de Trabajo de las Naciones Unidas sobre la Detención Arbitraria, Relator Especial sobre Libertad de Expresión, Relator Especial sobre Defensores de Derechos Humanos, Relator Especial sobre la Independencia de Jueces y Abogados y Relator Especial sobre Tortura. El texto destaca que el grupo de defensores de los derechos humanos saharauis fue arrestado y encarcelado en respuesta a su libertad de expresión y libertad de reunión en el campamento de Gdeim Izik. Aquí están los prisioneros de Gdeim Izik, uno por uno: Sidahmed Lemjeyid Nacido: 1959 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017  Sidahmed Lemjeyid nació el primero de marzo de 1959 en Smara, Sahara Occidental, que en ese momento todavía era una colonia española. Tenía 16 años cuando Marruecos invadió su país. Antes de ser encarcelado, Sidahmed vivió en El Aaiún. No está casado y no tiene hijos. Sidahmed dedica todo su tiempo a la causa saharaui. Es el presidente de CSPRON, el Comité para la Protección de los Recursos Naturales en el Sáhara Occidental, una organización que informa sobre el saqueo de los abundantes recursos naturales del Sáhara Occidental por parte de Marruecos. Como muchos saharauis, Sidahmed ha pagado un alto precio por hablar en contra de la potencia colonial marroquí. Fue detenido y encarcelado en 1999 por haber participado en grandes protestas en El Aaiún. Fue arrestado varias veces en 2005 y encarcelado durante algunos meses, nuevamente por participar en manifestaciones masivas a favor de la independencia. En relación con Gdeim Izik, fue arrestado por policías marroquíes vestidos de civil en El Aaiún el 25 de diciembre de 2010. Lo llevaron a un lugar desconocido donde lo interrogaron bajo tortura y lo obligaron a firmar una confesión escrita previamente, que nunca fue permitido leer. Lemjeiyd fue condenado a cadena perpetua en 2017 por un tribunal extraterritorial; y fue declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato y de asesinar a funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Lemjeiyd fue declarado culpable en ausencia de pruebas penales, ya que la principal prueba en su contra fueron los registros policiales firmados bajo tortura, respaldados por los testimonios de los policías que redactaron los informes ahora mencionados, y los testigos que Lemjeyid insta a declarar falsificados. testimonios. Nadie había oído hablar de los testigos antes mencionados antes de que fueran presentados ante el tribunal en 2017. Durante el proceso celebrado, Lemjeyid declaró al Tribunal de Apelación que no tenía nada que ver con el campamento y que solo había visitado el Gdeim Izik como activista de derechos humanos, donde había entrevistado a personas sobre sus demandas y su tolerancia. Declaró que todas las declaraciones estaban falsificadas y que no tenía nada que ver con ellas; sólo fue acusado por su activismo por los derechos humanos. Enaama Asfari Nacido: 1970 Sentenciado a 30 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Enaama Asfari nació en el seno de una familia saharaui en 1970 en Tan Tan, una localidad del sur de Marruecos. La familia de Enaama quedó destrozada cuando estalló la guerra por el Sáhara Occidental en 1975. Ese mismo año, las autoridades marroquíes encarcelaron a su padre, un conocido militante saharaui. Enaama era solo un niño de 5 años en ese momento. No volvería a ver a su padre hasta 1991, cuando Enaama tenía 21 años. Su madre había muerto mientras su padre estaba en la cárcel. En sus veintitantos años, con una licenciatura en derecho y economía internacionales, Enaama se mudó a París para realizar una maestría en relaciones internacionales. Sin olvidar la difícil situación de su pueblo, fundó el Comité para la Defensa de los Derechos Humanos en el Sáhara Occidental (CORELSO) con su esposa francesa. El activismo de Enaama conducía a arrestos cada vez que volvía a visitar a su familia, que se había mudado a El Aaiún, la capital del Sahara Occidental. Ha sido arrestado 6 veces en los últimos 7 años. En 2009, fue encarcelado durante 4 meses por sostener un llavero con la bandera saharaui. Enaama fue detenida el 7 de noviembre de 2010, en vísperas del desmantelamiento del campamento de Gdeim Izik. Estaba visitando a un amigo en El Aaiún, cuando la policía secreta marroquí vino a buscarlo. Lo llevaron a un lugar desconocido donde lo mantuvieron esposado y con los ojos vendados. El Comité contra la Tortura (CAT) determinó en una decisión relacionada con Enaama, de fecha 12 de diciembre de 2016, que Marruecos violó varios artículos enumerados en la Convención contra la tortura. Incluida la tortura durante la detención y el interrogatorio (artículo 1); falta de investigación (artículo 12); violación del derecho a la denuncia (artículo 13); obligación de indemnizar y reparar (art. 14); uso de confesiones obtenidas mediante tortura (art. 15); y trato inhumano durante la detención (art. 16). Como tal, la decisión establece claramente que Eênama Asfari ha sufrido torturas violentas y que el gobierno se ha abstenido de investigar esto. El 19 de julio, Asfari fue condenado a 30 años de prisión, condenado por participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con la intención de matar. El fiscal del Tribunal de Apelación de Salé describió a Asfari como el líder del campo de Gdeim Izik, descrito por el estado marroquí como un campo militar. La principal prueba contra Enaama fueron los registros policiales (confesiones), y las confesiones son la única prueba que prueba que Enaama de hecho estaba en el campamento de Gdeim Izik cuando fue desmantelado; contrariamente a lo que afirman el propio Eenaama y dos testigos de apoyo; que fue detenido el 7 de noviembre de 2010. Ahmed Sbai Fecha de nacimiento: 1978 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Ahmed Sbaai nació en El Aaiún, la capital del Sáhara Occidental ocupado, en 1971. Sbaai dice que las raíces de su activismo por los derechos humanos se remontan a la primera infancia, cuando sintió que él y sus amigos saharauis fueron discriminados por maestros marroquíes en las escuelas. Sbaai se volvió activo en 1999, durante la llamada Intifada Saharaui. Como él mismo ha manifestado: “Nuestros mandantes fueron que la intifada sería pacífica, hicimos banderas nacionales y las colgamos en instituciones marroquíes, también hicimos manifestaciones de dos minutos con banderas y gritos de consignas antes de dispersarnos antes de que la policía pudiera llevarnos. Es importante que el pueblo saharaui sepa que algunos hombres valientes estaban preparados para luchar «. Después de haber organizado grandes manifestaciones en El Aaiún en 2002, interrumpiendo así las elecciones de ese año, las autoridades marroquíes arrestaron a Sbaai. Fue condenado a diez años, pero fue puesto en libertad en 2004, después de haber pasado un año y tres meses en la célebre prisión negra de El Aaiún. Tras su liberación, Sbaai fundó la Liga Saharaui para la Protección de Presos Políticos dentro de las cárceles marroquíes. Fue detenido nuevamente en 2006 y condenado a un año y medio de prisión, acusado de ser miembro de una organización ilegal. Desde su liberación, no ha tenido un momento de paz. «Desde mi liberación he continuado con mi trabajo, me acosan a diario, me han confiscado el pasaporte, incluso hoy dos observadores de derechos humanos fueron sacados de mi casa. A veces me siento más seguro dentro de la prisión que fuera, al menos dentro hay guardias pero fuera de ellos [Marruecos] podrían contratar a alguien para que me matara «, ha dicho Sbaai en el pasado. Sbaai fue detenido por la policía marroquí el 8 de noviembre de 2010, en el barrio de Lirak, El Aaiún. Dice que no fue torturado físicamente, pero fue golpeado e intimidado durante el interrogatorio. Afirma que lo mantuvieron con los ojos vendados y esposado hasta que lo remitieron al tribunal militar de Rabat. El 19 de julio, Sbaai fue condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé. Sbaai fue condenado por formar una organización criminal y asesinar a funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con la intención de matar. La principal prueba que prueba el acto cometido por Sbaai son los antecedentes policiales; confesiones firmadas bajo tortura, que el propio Sbaai insta a que se falsifiquen en su contra. Sbaai declaró en el Tribunal de Apelación que el campamento de Gdeim Izik fue desmantelado por las fuerzas militares y que los enfrentamientos ocurridos fueron consecuencia del desmantelamiento violento del campamento de protesta pacífica, que estaba integrado por mujeres, niños y ancianos. Checikh Banga Nacido: 1989 Sentenciado a 30 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Cheikh Lkouri Bouzid Banga nació y se crió en Assa, al sur de Marruecos, hogar de una gran población saharaui que huyó hacia el norte cuando Marruecos invadió el Sahara Occidental. Cheikh creció en una familia cálida, con sus 2 hermanos y 5 hermanas. Al tener una mente para los libros, Cheikh le fue bien en la escuela, pero tuvo que abandonar debido a los repetidos encarcelamientos. Las autoridades marroquíes le prohibieron continuar sus estudios después de salir de prisión. A pesar de ello, está cursando su licenciatura en derecho desde la cárcel. Siempre ávido lector, le gusta especialmente el trabajo de Noam Chomsky. Cheikh es el preso de conciencia saharaui más joven. Ha sido arrestado muchas veces por defender el derecho a la autodeterminación de los saharauis. Es miembro de CODESA, presidente del Comité Saharaui de Derechos Humanos en Assa y miembro del capítulo local de Assa de AMDH (Asociación Marroquí de Derechos Humanos). A los 17 años, en 2006, pasó cinco meses en la cárcel de Anzigane. Apenas liberado, fue detenido nuevamente en El Aaiún en octubre de 2006 y condenado a 6 meses. Fue detenido el 8 de noviembre de 2010 en el campamento de Gdeim Izik. Acababa de llegar al lugar trayendo medicamentos para su tía, que había montado su tienda en el campamento de protesta. Cheikh fue torturado por la policía marroquí y obligado a firmar una confesión que no había podido leer de antemano. Banga fue condenado a 30 años de prisión por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. La principal prueba que acredita el acto cometido por Banga son los antecedentes policiales (confesiones), que el propio Banga declara falsificados y firmados bajo tortura. Banga declaró durante el proceso celebrado en el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé que las fuerzas públicas marroquíes atacaron a los habitantes del campamento mientras dormían, y que había sido agredido y secuestrado en su tienda el 8 de noviembre. El Bachir Khadda Nacimiento: 1986 Condenado a 20 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017  Bachir Elaabed Elmhtar El Khadda nació el 26 de octubre de 1986 en una familia saharaui que vivía en Tan Tan, una localidad del sur de Marruecos, cerca de la frontera con el Sáhara Occidental. Luego pasó a vivir en El Aaiún, la capital del Sahara Occidental. Bachir es miembro del Observatorio Saharaui de Derechos Humanos en el Sáhara Occidental. Cuando tenía 21 años, fue detenido y encarcelado para cumplir una pena de diez meses de prisión por haber participado en una manifestación independentista saharaui. Terminó sus niveles A mientras estaba en prisión. El 5 de diciembre de 2010, Bachir fue detenido en el café Las Dunas de El Aaiún, donde disfrutaba de un té con Hassan Dah y Mohamed Tahlil. Los tres hombres fueron llevados a la comisaría. Khadda dice que no fue torturado, pero dice que le vendaron los ojos y lo esposaron durante su detención. Khadda fue condenado a 20 años de prisión por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Khadda declaró que no estaba presente en el campo la mañana del 8 de noviembre e instó a que no cometiera los delitos de los que se le acusaba; y que los antecedentes policiales utilizados como prueba en su contra fueron falsificados y firmados bajo tortura. Durante sus declaraciones ante el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé, Khadda invocó la cuarta Convención de Ginebra y declaró que un tribunal marroquí no tenía competencia para juzgarlo. La principal prueba que prueba y describe los actos cometidos por Khadda son dichos registros policiales. Bachir está estudiando actualmente para obtener el título de abogado tras las rejas. Mohamed Tahlil Nacimiento: 1981 Condenado a 20 años por la Corte de Apelaciones de Salé en 2017.  Mohamed Tahlil nació en 1981 en Guelta Zemour, Sahara Occidental. Actualmente está registrado como habitante de Boujdour, donde vive solo. Tahlil es el presidente de la sección Boujdour de ASVDH, la Asociación Saharaui de Víctimas de Graves Violaciones de Derechos Humanos cometidas por el Estado marroquí. Fue encarcelado por su postura política en 2005 y 2007. En ambas ocasiones, fue sentenciado a tres años de cárcel, pero fue liberado después de un año y medio. Tahlil es el presidente de la sección Boujdour de ASVDH, la Asociación Saharaui de Víctimas de Graves Violaciones de Derechos Humanos cometidas por el Estado marroquí. Tahlil fue detenido junto con Bachir El Khadda y Hassan Dah el 5 de diciembre de 2010, mientras tomaban el té en el café Las Dunas de El Aaiún. Tahili dice que no ha sido sometido a tortura, pero sí sufrió abuso psicológico durante su interrogatorio cuando le vendaron los ojos y lo esposaron. Tahlil fue condenado a 20 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Thalil se declaró inocente de todos los cargos y denunció que el único motivo de su encarcelamiento eran sus opiniones políticas. Thalil instó a que no estuviera presente en el campamento durante las primeras horas del 8 de noviembre. La única prueba que prueba que Thalil estuvo presente en el campo durante la madrugada del 8 de noviembre son los registros policiales que todos los acusados instan a que sean falsificados y firmados bajo tortura. Hassan Eddah (Dah) Nacido en 1987  Condenado a 25 años (originalmente condenado a 30 años por el Tribunal Militar en 2013, reducido a 25 años en 2017 2017 por el Tribunal de Apelación) Hassan Dah nació el 18 de enero de 1987 en El Aaiún, donde creció en el barrio de Maatala, hogar de muchos saharauis que aún viven en la capital ocupada del Sáhara Occidental. Hassan es un defensor de los derechos humanos y está vinculado al Observatorio Saharaui de Derechos Humanos en el Sáhara Occidental. En 2007, pasó 10 meses en prisión por sus opiniones políticas. Terminó sus niveles A tras las rejas. La policía marroquí detuvo a Hassan Dah, Mohamed Tahlil y Bachir El Khadda el 5 de diciembre de 2010 en el café Las Dunas de El Aaiún. Hassan dice que lo han torturado física y psicológicamente, lo han mantenido con los ojos vendados y esposado, lo han violado con una porra, le han vertido agua fría y orina, además de varias otras violaciones de derechos humanos. Hassan Dah participó en el campamento de Gdeim Izik, donde actuó como corresponsal del servicio de radio y televisión del Frente Polisario, algo que el tribunal marroquí sostuvo contra él cuando lo acusó de atentar contra la seguridad del Estado. El Tribunal de Apelación de Salé condenó a Hassan Dah a 25 años de prisión el 19 de julio en ausencia flagrante de pruebas materiales. Hassan fue declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con la intención de matar Hassan describió a la corte cómo el 7 de noviembre había presenciado una caravana que traía comida y medicinas al campo, siendo detenida por las fuerzas militares. Hassan describió que había observado el asalto a la caravana como un activista de derechos humanos y describió cómo el campamento fue sitiado el 7 de noviembre y que las fuerzas militares impidieron que las personas salieran y entraran al campamento. Hassan declaró que estuvo en El Aaiún el 8 de noviembre y se declaró inocente de todos los cargos; declarando que el único motivo de su encarcelamiento fueron sus creencias políticas de que el pueblo del Sáhara Occidental tiene derecho a un referéndum sobre la autodeterminación. Mohamed Lamin Haddi Nacido: 1980 Condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Mohamed Lamin Haddi nació en 1984 en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental. Fue detenido por el servicio secreto marroquí el 20 de noviembre de 2010 en El Aaiún. Afirma no haber sido torturado, aunque dice que fue objeto de violaciones de derechos humanos mientras le vendaron los ojos, lo esposaron y le privaron de alimentos. Se cree que su detención estaba relacionada con la asistencia que había ofrecido a dos médicas belgas, Marie-Jeanne Wuidat y Ann Collier, que se encontraban en misión humanitaria en los territorios ocupados para brindar asistencia médica a las víctimas saharauis de la represión marroquí en Gdeim. Campamento de Izik. Tras el desmantelamiento del campo, el personal marroquí denegó la ayuda a muchos saharauis en el hospital de El Aaiún. Los médicos belgas fueron expulsados de El Aaiún. Mohammed Lamin Haddi declaró en el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé que se encontraba en El Aauin el 8 de noviembre y fue testigo de las protestas que surgieron tras el violento desmantelamiento del campamento. Haddi declaró que fue testigo de cómo se golpeaba a civiles en las calles, violaban a mujeres y vio cómo las fuerzas militares asaltaban a la gente en las calles. Haddi declaró que dos de sus amigos murieron ese día. Haddi fue condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Haddi instó a que la única razón de su encarcelamiento era su activismo por los derechos humanos, e instó a que él era inocente de todos los cargos. La única prueba que prueba o describe los presuntos actos cometidos por Haddi, o incluso su presencia en el campo, son los registros policiales que Haddi insta a que se falsifiquen en su contra y se firmen bajo tortura. Abdallahi Lakfawni Nacido: 1974 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Abdallahi Lakfawni nació en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental, en 1974. Abdallahi participó en el campamento de Gdeim Izik y contribuyó a mantener el campamento lo más organizado posible. El 5 de noviembre de 2010, el wali (gobernador) de El Aaiún quiso entrar en el campo, pero Lakfawni lo rechazó, incidente que, según se dice, fue la razón principal de su arresto y condena. Abdallahi detenido el 12 de noviembre de 2010 en la Playa de Foum El Oued, a 25 kilómetros al suroeste de El Aaiún. Abdallahi Lakfawni afirma haber sido sometido a diferentes tipos de tortura que le llevaron a perder el conocimiento durante su detención; lo obligaron a desvestirse, lo violaron con una porra, lo quemaron con cigarrillos en el cuerpo, lo sometieron a estrangulamiento falso, «el avión» y «pollo a la parrilla», y le vertieron orina en el cuerpo. A Abdallahi le vendaron los ojos mientras continuaba este terrible maltrato, y dice que lo privaron de sueño y comida. Lakfawni fue condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé, en ausencia de pruebas penales. Lakfawni fue declarado culpable de la formación de una organización criminal y culpable del asesinato de funcionarios públicos con la intención de matar. Lakfawni declaró que estuvo presente en el campo durante el desmantelamiento y explicó cómo el campo de Gdeim Izik estaba controlado con «mano de hierro» y cómo el campo estaba rodeado por personal militar, rodeado por un muro, con una sola entrada. Los militares habían hecho 7 puntos de control para que ingresáramos al campamento, declaró Lakfawni. Contó que estaba dormido cuando las fuerzas militares atacaron el campo y que fue como un terremoto, fue un caos, la gente corría y gritaba. Contó cómo las mujeres y los niños se desmayan debido a los gases lacrimógenos. Todos caminaron de regreso a la ciudad. Él afirmó: “Si Marruecos hubiera querido que supiéramos la verdad, habríamos tenido la verdad; pero lo han enterrado ”. Lakfawni se declaró inocente de todos los cargos e instó a que los registros policiales, la principal prueba de las acciones de Lakfawni, fueran falsificados y firmados bajo tortura. Abdallahi Toubali Nacido: 1980  Originalmente sentenciado a 25 años por un Tribunal Militar en 2013, reducido a 20 años en 2017. Abdallahi Toubali nació el 24 de marzo de 1980 en El Aaiún, la capital del Sahara Occidental ocupado. Abdallahi participó en el campamento de Gdeim Izik y fue miembro del Comité de Diálogo, que intentó negociar con las autoridades marroquíes para garantizar un mayor respeto por los agravios sociales y económicos de los residentes del campamento. Abdallahi fue atropellado por una camioneta de la policía el 7 de noviembre de 2010, la víspera del desmantelamiento del campamento. Fue trasladado al hospital de El Aaiún, pero se le negó la asistencia médica. Gracias a una intervención de Gachmoula Mint Ubbi, un desertor saharaui que ha sido elegido para el parlamento marroquí, Abdallahi fue ingresado para su primera atención en el hospital militar. Se le permitió irse a casa a las 2 am del 8 de noviembre de 2010. A las 9 am, Gachmoula vino a visitarlo. Abdallahi fue detenido el 2 de diciembre de 2010, acusado de haber asesinado a un policía marroquí en Gdeim Izik el 8 de noviembre, cuando en realidad se encontraba en su casa, recuperándose de ser atropellado por un todoterreno, en compañía de un parlamentario electo. Mientras estuvo detenido, Abdallahi fue sometido a tortura; lo violaron con una porra y le vertieron orina y agua fría en el cuerpo, mientras le vendaron los ojos, le esposaron las manos, lo desnudaron y lo sometieron a insultos y palizas. Toubali fue condenado a 20 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé el 19 de julio, condenado por participación a asesinato con intención de matar. Durante las audiencias, Toubali pidió repetidamente que se escuchara a Gachmoula Mint Ubbi como testigo, una solicitud denegada por el juez. Toubali instó a que no pudo haber cometido las acciones de las que se le acusaba, ya que estaba acostado en la cama de su casa en estado crítico, recuperándose de un accidente automovilístico. Toubali declaró que el único motivo de su detención era su papel en el Comité Dialouge, y explicó cómo el comité de diálogo había llegado a un acuerdo con las autoridades marroquíes el 6 de noviembre. Toubali explicó que se suponía que el gobierno debía venir al campamento el 8 de noviembre con carpas y registrar a los manifestantes para satisfacer sus demandas. Las autoridades marroquíes no cumplieron su promesa, pero atacaron el campamento a primera hora, mientras los habitantes dormían. La principal prueba que prueba la presencia de Toubail en el campo son los registros policiales, que Toubali insta a que se falsifiquen en su contra. El Houssin Ezzaoui Nacido: 1975 Condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  El Houssin Ezzaoui nació el 10 de octubre de 1975 en la familia de Fatma El Hussein y Boujema El Mahjoub, en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental. El Houssin todavía vive en El Aaiún con su esposa y dos hijos pequeños. Poseedor de un permiso de residencia español, El Houssin pasaba unos meses al año en España para ganarse la vida como trabajador temporal. El Houssin participó en el campamento de Gdeim Izik y fue miembro del Comité de Diálogo, una delegación de residentes del campamento que entabló conversaciones con el gobierno marroquí para obtener mejores condiciones de vida sociales y económicas para la población saharaui en el Sáhara Occidental ocupado. Fue detenido poco después de la medianoche del 2 de diciembre de 2010 en la casa del hermano de su esposa, Mohamed Al Saadi, en el barrio Al Amal de El Aaiún. Antes de ser interrogado, Ezzaoui dice que lo trataron de manera agresiva. Ezzaoui dice haber sido sometido a diversas formas de tortura física y psicológica mientras estaba detenido. Después de que le quitaron la ropa, lo violaron con el uso de una porra y le vertieron orina y agua fría en el cuerpo. Todo el tiempo que pasó en el exterior de la policía, lo vendaron los ojos y lo esposaron, lo sometieron a innumerables insultos y patadas, lo privaron de sueño, comida y agua. Ezzaoui fue por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé el 19 de julio condenado a 25 años de prisión, declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Ezzaoui explicó a la Corte cómo se había desmayado en la mañana del 8 de noviembre debido a los gases lacrimógenos liberados por las fuerzas públicas. Explicó cómo se despertó al día siguiente en el hospital, sin poder recordar nada del desmantelamiento del campamento. Ezzaoui instó a que no había realizado ninguna de las acciones de las que se le acusaba, e instó a que solo fuera encarcelado por estas opiniones políticas y su papel en el comité de diálogo. Ezzaoui fue condenado por falta de pruebas penales, ya que la principal prueba de los hechos cometidos eran los antecedentes policiales. Mohamed Bourial Nacido: 1976 Sentenciado a 30 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Mohamed Bourial nació en 1970, en El Aaiún, la capital del «Sahara español», como se conocía al Sáhara Occidental durante el reinado colonial español. Pasarían otros 5 años antes de que Marruecos asumiera el papel de potencia colonial en el territorio. Mohamed Bourial está casado y tiene 2 hijos. Su familia vive en El Aaiún. Mohamed trató de ganarse la vida y ocasionalmente encuentra un trabajo remunerado a corto plazo, pero no tiene un empleo fijo ni ingresos. Cansados de la desesperada situación en la que muchos saharauis se ven obligados a vivir bajo la ocupación marroquí, Mohamed y su familia montaron su tienda de campaña en el campamento de Gdeim Izik. Mohamed se convirtió en miembro del llamado Comité de Diálogo; un grupo de representantes del campo que se reunió regularmente y negoció con las autoridades marroquíes para tratar de asegurar mejores condiciones de vida para el pueblo saharaui en su propia tierra. Fue detenido por el ejército marroquí el 8 de noviembre de 2010 en el campamento. Fue trasladado al cuartel general del ejército en El Aaiún. Allí, pasó cinco días con los ojos vendados, desnudo y sometido a brutales palizas con un cable de acero. Mohamed Bourial, condenado a 30 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017, declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Bourial actuó como titular del comité de diálogo y explicó a la Corte de Apelaciones cómo el comité de diálogo y el gobierno habían llegado a un acuerdo con dos días de anticipación. Se esperaba que el ministro de Infraestructura se presentara en el campamento con 9 carpas para organizar un conteo de la población en el campamento, para que el gobierno pudiera atender las demandas sociales planteadas por el habitante. El gobierno no cumplió su promesa y el habitante del campamento se sorprendió por su ataque; que tuvo lugar a las 6 de la madrugada del 8 de noviembre. Bourial declaró al tribunal que “El campo de Gdeim Izik reveló la política del ocupante de Marruecos y cómo margina a la gente del Sahara Occidental y roba nuestros recursos. El campamento de Gdeim Izik es producto de la marginación de todos los saharauis y de la ocupación del Sáhara Occidental por Marruecos. El campamento duró 28 días. No hubo crimen. Sin violencia. Marruecos atacó el 8 de noviembre a mujeres, niños, ancianos y hombres ”. Bourial declaró en el Tribunal de Apelación que era inocente de todos los cargos, e instó a que los registros policiales sean falsificados y que no conocía su contenido hasta que fue juzgado en el Tribunal Militar de Rabat en 2013. La policía mencionada Los registros son la principal prueba de los actos cometidos por Bourial, y según Bourial fueron falsificados y firmados bajo tortura. Laaroussi Abdeljalil Nacido: 1978 Sentenciado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Sidi Laaroussi Abdeljalil nació en El Aaiún en 1978, hijo de Kamel Mohamed y Monina Cori. Sus padres viven actualmente en Boujdour, unos 170 kilómetros más al sur, pero Laaroussi se quedó en El Aaiún donde formó una familia propia; es padre de dos niños pequeños. Con su esposo y proveedor desaparecidos, la esposa de Laaroussi se ha llevado a sus hijos y se ha mudado con sus padres. La vida no ha sido fácil para Laaroussi, quien, como sostén de su familia, luchó por encontrar un empleo estable. Como miles de otros saharauis, fue la marginación social y económica lo que lo llevó al campamento de Gdeim Izik. El 13 de noviembre de 2010, cinco días después de que el ejército marroquí incendiara el campamento, Laaroussi fue detenido en la casa de sus padres en Boujdour. Fue trasladado a la comisaría de El Aaiún donde fue objeto de graves violaciones de derechos humanos durante su detención. Pasó cuatro días desnudo, con los ojos vendados y esposado, fue torturado, electrocutado y amenazado con violarlo. La policía amenazó con llevar a su esposa a la comisaría y violarla ante los mismos ojos de Laaroussi. El maltrato ha tenido sus efectos: Laaroussi todavía tiene dificultad para caminar debido a la pérdida del equilibrio. Durante la visita del Comité de la ONU sobre Detención Arbitraria en 2013, Laroussi fue separado del resto del grupo y colocado con los delincuentes comunes. Laroussi fue condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación el 19 de julio y declarado culpable de la formación de una organización criminal y el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. El fiscal afirmó que Laroussi supervisaba las fuerzas de seguridad en el campamento de Gdeim Izik, que según el fiscal era un campamento militar, con el objetivo de desestabilizar la región. Laroussi declaró ante el tribunal que visitó dos veces el campamento Gdeim Izik, donde visitó a su tía. El 7 de noviembre de 2010 Laaroussi se encontraba en Bojador para cuidar a su madre enferma, y Laroussi declaró que permaneció en Bojador hasta el 12 de noviembre, cuando fue detenido por funcionarios públicos que irrumpieron en la casa de su prima. La principal prueba contra Laroussi son los antecedentes policiales, que implican confesiones firmadas bajo tortura. Todos los acusados instan a que se falsifiquen los antecedentes policiales en su contra y que el gobierno marroquí está encubriendo la verdad sobre cómo en la madrugada del 8 de noviembre atacaron a miles de civiles mientras dormían. Mohamed El Bachir Boutinguiza Nacido en 1974 Sentenciado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Mohamed El Bachir Boutinguiza nació en El Aaiún en 1974. Su madre Mailemenin, quien viajó cientos de kilómetros desde El Aaiún hasta Salé para poder ver a su hijo dos veces por semana en prisión, recuerda su año de nacimiento como el año antes de que los marroquíes invadieran Occidente. Sáhara. Mohamed no está casado y no tiene hijos. Como tiene permiso de residencia español, pasa unos meses al año en España para ganarse la vida como trabajador temporero. El trabajo en el Sáhara Occidental es difícil de conseguir para la mayoría de los saharauis, debido al trato preferencial de los colonos marroquíes. El trabajo temporal en el extranjero le permite a Mohamed ayudar a mantener a su familia en El Aaiún. Al igual que su madre, Mohamed Boutinguiza participó en el campamento de protesta de Gdeim Izik. Fue detenido el 19 de noviembre de 2010 por la policía marroquí en el barrio Linaach de El Aaiún. Boutinguiza dice haber sido sometido a varios tipos de tortura. Antes de que la policía lo llevara a la comisaría de El Aaiún, Boutinguiza fue violado con un objeto metálico. Durante su detención en la estación de policía, Boutinguiza fue interrogado mientras le vendaron los ojos, lo esposaron y le quitaron la ropa. Fue sometido a electrochoques, insultos y privado de sueño y comida. Boutinguiza fue condenado a cadena perpetua por la Corte de Apelaciones y declarado culpable de la formación de una organización criminal y el asesinato de un funcionario público en el cumplimiento del deber, con intención de matar. Al igual que el resto de los 19 detenidos, Boutinguiza ha estado en detención arbitraria durante casi siete años, y sigue sufriendo tratos inhumanos y acoso constante. Boutinguiza declaró ante el tribunal que no se encontraba en el campamento cuando fue destruido; donde no pudo haber cometido el crimen porque estuvo en El Aaiún en la boda de un amigo. La principal prueba que prueba el delito son los antecedentes policiales. Los antecedentes policiales implican confesiones que los acusados instan a ser falsificadas en su contra y firmadas bajo tortura. Boutinguiza declaró que era inocente y capturado por sus opiniones políticas. Mohamed Bani Nacido: 1969 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017  Mohamed Bani nació en El Aaiún, la capital del Sáhara Occidental ocupado, en 1969. Casado y padre de cinco hijos, Bani fue uno de los pocos saharauis que tuvo la suerte haber encontrado empleo en un sistema que tiende a preferir a los colonos marroquíes a los saharauis. Bani trabajó en el Ministerio de Infraestructura. El Sr. Bani no formaba parte del campamento de protesta Gdeim Izik, pero tenía muchos familiares en el campamento. Visitó a su familia el domingo 7 de noviembre y fue detenido cuando intentaba irse. El 8 de noviembre, cuando intentaba salir, la policía lo detuvo acusándolo de atropellar a un oficial. Había visitado a su familia el domingo 7 de noviembre, el día antes de que el campamento fuera reducido a cenizas. Cuando trató de irse por la noche, fue detenido por la policía y el ejército marroquíes, que habían sellado los alrededores del campamento. Cuando Mohamed intentó marcharse de nuevo a la mañana siguiente, la policía lo arrestó y lo acusó de haber atropellado a los agentes. Bani fue sometido a torturas físicas y psicológicas mientras estaba detenido; después de haber sufrido un traumatismo craneoencefálico grave causado por golpes excesivos, pasó seis días sin ningún tipo de asistencia médica, pero con los ojos vendados, esposado, privado de sueño y comida, y le vertieron orina. Las heridas no han sanado y Mohamed sigue teniendo problemas como resultado de la lesión en la cabeza hasta el día de hoy. Bani fue condenado el 19 de julio de 2017 a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé. El fiscal provocó nuevos testigos durante el proceso que se llevó a cabo en la Corte de Apelaciones, y testigos que carecían de la credibilidad necesaria y sin un proceso de identificación legal, describieron cómo Bani había atacado a las fuerzas militares con su automóvil. Bani, por su parte, instó a que en la mañana del 8 de noviembre se dirigía de regreso a la ciudad para llevar a sus hijos a la escuela, que su automóvil había sido golpeado por piedras y que perdió el conocimiento cuando lo golpearon. en la cabeza con una piedra. Bani insta a que no atacó a las fuerzas militares con su automóvil y que fue derrocado cuando su automóvil fue golpeado con piedras. Bani fue condenado por la formación de una organización criminal y por asesinato con intención de matar; Sidi Abdallah B’hah Nacido: 1975 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017  Sidi Abdallah B’hah nació en El Aaiún en 1975, el año de la llamada Marcha Verde, cuando Marruecos invadió su vecino del sur del Sahara Occidental. . Sidi aún vive en El Aaiún, pero su permiso de residencia español le permite trabajar en España como trabajador temporero. El 19 de noviembre de 2010, Sidi fue detenido en el barrio Linaach de El Aaiún. Dice que lo mantuvieron con los ojos vendados, esposado y desnudo durante los interrogatorios en la estación de policía, le vertieron orina y lo privaron del sueño, ya que lo obligaron a pararse contra una pared sin moverse. Sidi Abdallah B’hah fue condenado a cadena perpetua el 19 de julio de 2017; declarado culpable de la formación de una organización criminal y asesinato de funcionarios públicos, con la intención de matar. Sidi declaró que no estuvo presente en el campo durante el violento desmantelamiento del campo de protesta pacífica. Sidi insta a que la única razón de su encarcelamiento son sus opiniones políticas, y que los registros policiales están falsificados en su contra y firmados bajo tortura. La principal prueba que demuestra que Sidi incluso estuvo en el campamento de Gdeim Izik el 8 de noviembre son los registros policiales. Brahim Ismaïli Nacimiento: 1970 Condenado a cadena perpetua por el Tribunal de Apelaciones de Salé en 2017  Brahim Ismaili nació y se crió en 1970 en El Aaiún. Brahim es el presidente del Centro de Preservación de la memoria colectiva saharaui. Brahim fue detenido el 9 de noviembre de 2010 en su casa del barrio de Zemla, en presencia de su esposa Alfan y dos de sus cuatro hijos. Fue llevado a la célebre prisión negra de El Aaiún. Después de 7 meses, el 13 de mayo de 2011, Brahim fue liberado junto con otros saharauis. Pero justo afuera de las puertas de la prisión, la policía lo arrestó nuevamente y lo llevó a la prisión de Salé, a 1.200 kilómetros al norte de Marruecos. No es la primera vez que Brahim Ismaili está en la cárcel por sus opiniones políticas. En 1987, fue secuestrado y mantenido en un centro de detención secreto durante meses. El 19 de julio de 2017, Brahim fue condenado a cadena perpetua y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato y asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con la intención de matar. Brahim declaró que el expediente policial, que sirve como principal prueba en su contra, está falsificado y firmado bajo tortura. Brahim declaró que durante todos los interrogatorios se le preguntó sobre su activismo por la autodeterminación y su viaje a Argelia, e instó a que nunca le hicieran preguntas sobre el Gdeim Izik. Explicó cómo fue a Argelia, en agosto de 2010, con una delegación para asistir a una conferencia internacional sobre el derecho a la autodeterminación, donde el Sáhara Occidental sirvió de modelo. Brahim explicó además que no estaba en el campamento durante el ataque, Cuando se le preguntó sobre el supuesto comité de seguridad dentro del campo, Brahimi afirmó que “nunca he visto ningún comité. El campamento de Gdeim Izik estaba rodeado por militares. Tenía una sola entrada. Tuvimos que pasar por siete puestos de control para llegar a los campamentos y mostrar nuestra identidad. No tengo información ”. Mohamed Embarek Lefkir Nacido: 1978 Condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017.  Mohamed Embarek Lefkir nació en 1975 en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental. No está casado y no tiene hijos. El 12 de noviembre de 2010, Mohamed fue detenido por su participación en el campamento de Gdeim Izik. Fue trasladado a la cárcel de Black en El Aaiún, donde estuvo detenido hasta el 17 de junio de 2011, cuando fue liberado temporalmente. Pero una vez liberado, la policía lo arrestó y lo llevó a la prisión de Salé, en Marruecos, a unos 1200 kilómetros al norte de El Aaiún. Antes de montar su tienda en Gdeim Izik, Mohamed formaba parte de una delegación de defensores de los derechos humanos saharauis que habían sido invitados a Argel por el Frente Polisario, el movimiento de liberación saharaui con sede en los campos de refugiados argelinos. Lefkir fue condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación el 19 de julio; y declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Durante el interrogatorio de Lefkir el 22 de marzo, Lefkir declaró, recibido con gritos de la fiscalía, que; “Condeno la política de hambre que está liderando el ocupante de Marruecos y la política de las empresas extranjeras que apoyan a las fuerzas de ocupación marroquíes”. Lefkir declaró que en las primeras horas del ataque se había desmayado debido a los gases lacrimógenos y que fue llevado por su familia durante 4 kilómetros, y luego caminó los 8 kilómetros restantes hasta su casa en El Aiun. La principal prueba que prueba las acciones de Lefkir son los registros policiales que contienen confesiones que Lefkir declaró falsificadas y firmadas bajo tortura y amenazas. Cuando el juez le preguntó a Lefkir por qué había firmado las declaraciones ante el juez de instrucción, Lefkir declaró que los guardias, con el juez presente, declararon que: “Si no firmas, te enviaré de regreso y estarás torturado más y peor de lo que ya has soportado «. Explicó cómo había negado todos los cargos al juez y le explicó que fue arrestado por su activismo. Lefkir declaró que el juez “me preguntó si podía perdonarlo. Dijo que esto me supera; Solo sigo órdenes «. Lefkir fue condenado por el Tribunal de Apelación sobre la base de estos antecedentes policiales y en ausencia flagrante de pruebas penales. Babait Mohamed Khuna Nacido: 1981 Condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017  Babait Mohamed Khuna nació el 24 de octubre de 1981 en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental. Babait aún vive en El Aaiún y es uno de los pocos saharauis que tuvo la suerte de encontrar un empleo local: Babait trabajaba para la administración local. Sin embargo, siempre sintió un fuerte sentido de solidaridad con los menos afortunados. Tras el violento desmantelamiento del campo de protesta de Gdeim Izik y las detenciones masivas de ciudadanos saharauis, Babait participó a menudo en manifestaciones que exigían la liberación de los prisioneros. Su jefe en la administración local había intentado impedirle asistir a esos mítines, hasta el punto de amenazar con dimitir, pero Babait continuó participando en las marchas de protesta. El 15 de agosto de 2011, Babait fue detenido en El Aaiún por la policía marroquí. El 19 de julio Babait fue condenado a 25 años por la Corte de Apelaciones, declarado culpable de participación en el asesinato y asesinato de funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber, con intención de matar. Babait declaró al tribunal que no estaba en el campamento durante los hechos y que no tenía ninguna relación con el campamento, aparte de su madre, que tenía una tienda de campaña en el campamento. La principal prueba contra Babait son los registros policiales. Babait declara que fue obligado a firmar los registros policiales bajo amenazas, y que la policía había dejado espacios en blanco en las páginas y que la policía los completó en una oportunidad posterior. Deich Eddaf Nacimiento: 1978  Inicialmente sentenciado a 25 años por el Tribunal Militar en 2013, reducido a 6,5 años en 2017, liberado el 19 de julio de 2017 Deich Eddaf nació el 11 de mayo de 1978 en El Aaiún, Sahara Occidental. Está casado y es padre de un niño. Deich era uno de los miles de saharauis que habían montado sus tiendas en Gdeim Izik. Como miembro del Comité de Diálogo Gdeim Izik, participó en conversaciones con las autoridades marroquíes para alcanzar mejores condiciones sociales y económicas para el pueblo saharaui que vive bajo la ocupación marroquí. Deich fue detenido en su domicilio por la policía marroquí el 3 de diciembre de 2010. En la comisaría de El Aaiún ha sido torturado, despojado de su ropa, orinado y violado con el uso de una porra. Pasó el tiempo detenido desnudo, con los ojos vendados, esposado y privado de sueño, comida y agua. Deich tiene cicatrices de tortura visibles en todo el cuerpo. Deich Eddaf fue condenado a 6 años y medio por el Tribunal de Apelaciones de Salé en 2017. Fue liberado el 19 de julio de 2017 y declarado culpable de violencia contra funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber. Sidi Abderahman Zeyou Nacimiento: 1974 Condenado en 2017 a dos años de prisión, tiempo que ya había cumplido cuando fue liberado en 2013.  Sidi Abderahmane Zeyou es uno de los dos de los 25 presos de Gdeim Izik que fueron condenados por el tiempo que pasaron en prisión preventiva y, por lo tanto, fueron puestos en libertad, lo que le permitió reunirse con su hija. Sidi nació en El Aaiún, la capital del Sahara Occidental, en 1974, un año antes de que el ejército marroquí invadiera el territorio. Para ser un saharaui que vivía bajo la ocupación marroquí, a Sidi le fue notablemente bien: pudo obtener un título en economía y logró encontrar empleo en el ayuntamiento de El Aaiún. Aunque no participó en el campamento de Gdeim Izik, visitó el sitio con frecuencia. Sidi es el presidente del comité des cadres sahraouis, un grupo que se encargó de suministrar alimentos y medicinas al campamento. El 21 de noviembre, tras haber terminado su último día de trabajo antes de partir de vacaciones a España, Sidi fue detenido en el aeropuerto de El Aaiún. La policía tenía una orden judicial en su contra, emitida por el fiscal del Tribunal de Apelación, a raíz de la participación de Sidi en Gdeim Izik. Sidi dice que lo torturaron durante la detención, pero lo trataron mal porque lo mantuvieron con los ojos vendados y esposado todo el tiempo. Sidi Abderahmane Zeyou fue condenado por el tiempo que pasó en prisión preventiva y, por tanto, puesto en libertad el 17 de febrero de 2013, cuando el tribunal militar de Rabat condenó a sus amigos a penas terriblemente duras. Zeyou fue declarado culpable de violencia contra funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé el 19 de julio y condenado a dos años. Machdoufi Ettaki Nacimiento: 1985  Condenado en 2017 a dos años de prisión, tiempo que ya había cumplido cuando fue puesto en libertad en 2013. Machdoufi Ettaki nació el 11 de marzo de 1985 en Tan Tan, una localidad del sur de Marruecos con una gran población saharaui. Ettaki vive actualmente en El Aaiún. Solía trabajar como soldado en el ejército marroquí, pero fue expulsado en 2009 por no seguir órdenes. Después de cuatro meses de prisión fue expulsado del ejército. Ha estado desempleado desde entonces. El 8 de noviembre de 2010, Ettaki fue detenido por la policía marroquí en el campamento de Gdeim Izik. Lo llevaron a la comisaría, donde lo torturaron durante seis días mientras le vendaron los ojos, lo esposaron y le quitaron la ropa. La policía le arrojó orina y lo golpeó con tanta fuerza que tuvo que ser transportado al hospital dos veces. Ettaki fue puesto en libertad el 17 de febrero de 2013, mientras que los otros 23 fueron condenados a penas extremadamente duras. Ettaki fue declarado culpable de actos de violencia contra funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber por el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé el 19 de julio y condenado a dos años. Larabi El Bakay Nacido: 1982  Sentenciado a 4,5 años por el Tribunal de Apelaciones de Salé en 2017. Liberado el 19 de julio de 2017. Originalmente condenado a 25 años por el Tribunal Militar en 2013. Larabi El Bakay es nativo de El Aaiún; nació allí en 1982 y permaneció allí desde entonces. Larabi está casado y es padre de dos hijos. Larabi tuvo dificultades para llegar a fin de mes y, en ocasiones, encontró un trabajo temporal en el sector pesquero de Dakhla. Larabi y su familia habían levantado su tienda en Gdeim Izik, para denunciar las miserables condiciones socioeconómicas que enfrentan muchos saharauis en su tierra ocupada. Tanto Larabi como su esposa participaron en el Comité de Diálogo, que mantuvo conversaciones periódicas con las autoridades marroquíes para negociar condiciones de vida más favorables para los saharauis. Casi dos años después de que el ejército marroquí incendiara el campo, Larabi y su esposa fueron arrestados el 9 de septiembre de 2012. Su esposa fue puesta en libertad después de 48 horas de interrogatorio. El Bakay fue sentenciado a cuatro años y medio por la Corte de Apelaciones de Salé en 2017 y declarado culpable de violencia hacia funcionarios públicos en el cumplimiento de su deber. Quedó en libertad el 19 de julio de 2017. Mohamed El Ayoubi Nacimiento: 1956  Condenado a 20 años en libertad provisional debido a su estado de salud debilitado por el Tribunal Militar en 2013. Mohamed murió el 21 de febrero de 2018. Se cree que su muerte se debe a las torturas que sufrió Mohamed durante el tiempo que pasó en prisión. Mohamed El Ayubi nació el 18 de noviembre de 1955 en El Aaiún, la capital del Sahara Occidental, que en ese momento todavía era una colonia española. Mohamed nunca se casó y no tuvo hijos. Sufría de un trastorno mental que se originó en la primera infancia. Mohamed se había alojado en el campamento de Gdeim Izik y fue detenido allí por el ejército marroquí el 8 de noviembre de 2010. Ha sufrido un trato inhumano mientras estuvo detenido; lo violaron con un garrote, la policía le echó agua fría y orina sobre él y lo golpeó en las plantas de los pies. Todo el tiempo estuvo con los ojos vendados, esposado y desnudo. Según su hermana Aisha y su abogado, Mohamed tuvo dificultades para hablar como resultado de las torturas que le infligieron. Varias otras lesiones, como una mano rota, no fueron atendidas mientras estuvo detenido. Ayoubi tenía insuficiencia renal y problemas cardíacos. Durante el proceso judicial del nuevo juicio de Gdeim Izik ante un tribunal civil, tuvo dificultades para caminar y hablar, y para levantar los brazos después de la tortura a la que fue sometido. Debido a sus problemas de salud, Mohamed fue puesto en libertad provisional el 13 de diciembre de 2011. Sin embargo, el 17 de febrero de 2013, el tribunal militar marroquí de Rabat lo condenó a 20 años de prisión. El caso de Mohamed El Ayubi se separó del caso colectivo en junio de 2017 y su caso estaba programado para el 27 de septiembre de 2017 en la Corte de Apelaciones de Salé. El caso judicial de Auybi se pospuso el 27 de septiembre hasta el 15 de noviembre de 2017. Hassana Alia Nacimiento: 1989  Condenado a cadena perpetua en rebeldía por el Tribunal Militar en 2013. Hassana obtuvo asilo político en España. Hassana Alia no fue citada a comparecer ante el Tribunal de Apelación de Salé en 2017. «Que me condenen a cadena perpetua no me duele», dice Hassana, «lo que realmente me duele es que no podré volver a ver a mis padres, hermanos y hermanas». Hassana Alia, nacida en 1989, es la que se escapó. Hassana escuchó por radio el veredicto del Tribunal Militar, en el País Vasco, España, donde vive hoy. No le molesta que las autoridades marroquíes conozcan su paradero. «No me voy a esconder», dice. «Me detuvieron en 2010 mientras nos desalojaban del campamento de Gdeim Izik. La policía marroquí me liberó dos veces, porque no tenían pruebas en mi contra. Me dieron un visado para salir del país sin ninguna dificultad. Ahora han condenado por algo que dijeron anteriormente que no hice «. Hassana ahora dedica su vida a crear conciencia sobre sus amigos que están en la cárcel, condenados a duras penas por los mismos motivos que él. Es militante, pero su mirada comienza a nublarse cuando le preguntan si le gustaría volver. Hassana respira hondo y dice «ahora no. Me encantaría ver a mis padres, mis hermanos y hermanas, mi gente, mi país, pero si terminara en la cárcel, no me quedaría nada por hacer». . Desde el exterior, puedo contarle al mundo lo que les ha pasado a mis amigos y luchar por ellos. |

In november 2020, a group of Saharawi political prisoners referred to as the Gdeim Izik group, will have spent 10 years in Moroccan jails. In anticipation of the upcoming tragic anniversary, WSRW calls for the immediate and unconditional release of these political prisoners.

In the early morning of 8 November 2010 – a week before the Arab spring would ignite – the Moroccan army and police brutally tore down a peaceful protest camp, where over 10,000 Saharawis had gathered in protest of their socio-economic exclusion in their own homeland that is under Moroccan occupation. The location of the camp was at a site called Gdeim Izik, a desert area outside of the capital city El Aaiún.

As the camp was burnt to the ground, fights erupted between police and frustrated Saharawis. Both police officers and civilian Saharawis died during the clashes. A group of 25 men was arrested over their supposed participation in the organisation of the protest camp. After two and a half years in arbitrary detention, they were sentenced in February 2013 in a Moroccan military court, most to sentences ranging between 20 years and lifetime.

Among the arrested were leading human rights defenders from Western Sahara. One of them is the secretary-general of a Saharawi group that monitors the foreign involvement in Morocco’s illegal plunder of the territory.

The main piece of criminal evidence used against them consisted of confessions, signed under torture. The verdict rendered was appealed to the Moroccan Court of Cassation holding that the court could not condemn this group of activists solely on the basis of confessions. Four years later, in 2017, the case was therefore re-tried in front of a civilian court with the sentences being mostly upheld, and the confessions signed under torture being re-used as main criminal evidence. The case was therefore once again appealed to the Moroccan Court of Cassation which has not yet rendered a decision.

Today, 19 of the 25 are still in prison. Their trial was a travesty of justice. The only prove against the men were confessions given under torture. Here is a report on the Kafkaesque trial against the group. The report analyses the evidence and arguments used by the court.

“The breach of the international law on the right to a fair trial in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and of Morocco’s other international obligations renders the deprivation of liberty of the 19 detainees arbitrary. The 19 detainees were subjected to abductions or arrest involving torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment. Their unlawful treatment has continued during their detention. The group has been detained for some seven years. Their conviction was not based on sufficient criminal material evidence,” former head of the UN Committee on Arbitrary detention, Mads Andenæs, stated in the foreword to the above report.

“These men have done nothing but peacefully advocate for their basic human rights. They have spent 10 years of their lives imprisoned based on trials that failed to follow the most basic international standards. We call on the international community to put pressure on Morocco for their immediate and unconditional release», says Sylvia Valentin, Chair of Western Sahara Resource Watch.

The arbitrary detainment of the Gdeim Izik prisoners was, amongst other, treated in a communication issued by the United Nations Special Procedures on 20 July 2017 (AL Mar 3/2017), signed by the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Expression, Special Rapporteur on Human Rights Defenders, Special Rapporteur on the Independence of Judges and Lawyers and the Special Rapporteur on Torture. The text stresses that the group of Saharawi human rights defenders had been arrested and detained in response to their freedom of expression and freedom of assembly in the Gdeim Izik camp.

Here are the Gdeim Izik prisoners, one by one:

Sidahmed Lemjeyid

Born: 1959

Sentenced to life by the Court of Appeal in Salé in 2017

Sidahmed Lemjeyid was born on the first of March 1959 in Smara, Western Sahara, which at the time was still a Spanish colony. He was 16 years old when Morocco invaded his country. Before being imprisoned, Sidahmed lived in El Aaiún. He is not married and has no children.

Sidahmed dedicates all his time to the Saharawi cause. He is the President of CSPRON, the Committee for the Protection of Natural Resources in Western Sahara – an organisation that reports on the plundering of Western Sahara’s abundant natural resources by Morocco.

Like many Saharawis, Sidahmed has paid a heavy price for speaking out against the Moroccan colonial power. He was arrested and jailed in 1999 for having participated in large protests in El Aaiún. He was arrested several times in 2005 and jailed for a few months, again for taking part in massive pro-independence demonstrations.

In relation to Gdeim Izik, he was arrested by plain-clothed Moroccan policemen in El Aaiún on 25 December 2010. He was taken to an unknown location where he was interrogated under torture and forced to sign a pre-written confession, that he was never allowed to read.

Lemjeiyd was condemned to life in prison in 2017 by an extraterritorial court; and was found guilty of participation to murder and of murdering public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill. Lemjeiyd was found guilty in the absence of criminal evidence, as the main piece of evidence against him were the police records signed under torture, supported by the testimonies from the police men which wrote the now mentioned reports, and witnesses that Lemjeyid urges are declaring falsified testimonies. No one had ever heard about the aforementioned witnesses before they were presented in front of the court in 2017. During the proceedings held, Lemjeyid declared to the Court of Appeal that he had nothing to do with the camp, and that he had only visited the Gdeim Izik as a human rights activist, where he had interviewed people about their demands and their sufferance. He declared that all the statements were falsified, and that he had nothing to do with them; he was only accused because of his human rights activism.

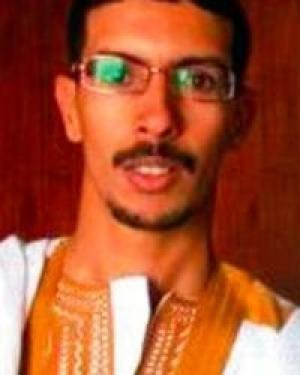

Enaama Asfari

Born: 1970

Sentenced to 30 years by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Enaama Asfari was born to a Saharawi family in 1970 in Tan Tan, a town in the south of Morocco. Enaama’s family was torn apart when the war over Western Sahara broke out in 1975. In that same year, the Moroccan authorities imprisoned his father, a known Saharawi militant. Enaama was only a 5-year-old boy at the time. He would not see his father again until 1991, when Enaama was 21. His mother had died while his father was in jail.

In his late twenties, holding a degree in international law and economics, Enaama moved to Paris to pursue a master in international relations. Not forgetting the plight of his people, he founded the Committee for the Defence of Human Rights in Western Sahara (CORELSO) with his French wife.

Enaama’s activism would lead to arrests whenever he’d go back to visit his family, that had relocated to El Aaiún, the capital of Western Sahara. He’s been arrested 6 times over the past 7 years. In 2009, he was thrown in prison for 4 months over holding a keychain that depicted the Saharawi flag.

Enaama was arrested on 7 November 2010, on the eve of the dismantlement of the Gdeim Izik camp. He was visiting a friend in El Aaiún, when the Moroccan secret police came for him. He was taken to an unknown location where he held blindfolded and handcuffed.

The Committee against Torture (CAT) found in a decision related to Enaama, dated 12 December 2016, that Morocco was in violation of multiple articles listed in the Convention against torture. Including torture during arrest and interrogation (art.1); failure to investigate (art.12); violation of the right to complain (art.13); obligation to compensate and reparation (art.14); usage of confessions obtained through torture (art. 15); and inhuman treatment in detention (art. 16). As such, the decision clearly states that Eênama Asfari has suffered under violent torture, and that the government has refrained from investigating this.

On the 19th of July, Asfari was sentenced to 30 years in prison, condemned for participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with the intent to kill. The prosecutor in the Appeal Court of Salé described Asfari as the leader of the Gdeim Izik camp, described by the Moroccan state as a military camp. The main evidence against Enaama was the police records (confessions), and the confessions is the sole piece of evidence proving that Enaama in fact was in the Gdeim Izik camp when it was dismantled; contrary to what Eenaama himself and two support witnesses states; that he was arrested on 7 November 2010.

Ahmed Sbai

Born: 1978

Sentenced to life imprisonment by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Ahmed Sbaai was born in El Aaiún, the capital of occupied Western Sahara, in 1971. Sbaai says the roots for his human rights activism can be traced back to early childhood, when he felt that he and his Saharawi friends were discriminated by Moroccan teachers in the schools.

Sbaai became active in 1999, during the so-called Saharawi Intifada. As he has stated himself: «Our principals were that the intifada would be peaceful, we made national flags and hung them in Moroccan institutions, we also held two minute demonstrations with flags and shouting slogans before dispersing before the police could take us. It was important for the Saharawi people to know some brave men were prepared to fight.»

After having organised big demonstrations in El Aaiún in 2002, thereby disrupting the elections that year, the Moroccan authorities arrested Sbaai. He was sentenced to ten years, but was released in 2004, after having spent a year and three months in the notorious black prison in El Aaiún.

Upon his release, Sbaai founded the Saharawi League for the Protection of Political Prisoners inside Moroccan Jails. He was arrested again in 2006 and sentenced to a year and half in prison, accused of being a member of an illegal organisation. Since his releace, he’s not had a moment of peace.

«Since my release I have continued my work, I am harassed daily, my passport has been confiscated, even today two human rights observers were removed from my home. Sometimes I feel I was more safe inside prison than outside, at least inside there are guards but outside they [Morocco] could hire someone to kill me», Sbaai has said in the past.

Sbaai was arrested by the Moroccan police on 8 November 2010, in the Lirak neighbourhood, El Aaiún. He says he was not physically tortured, but was beaten and intimidated during his interrogation. He claims to have been kept blindfolded and handcuffed until he was referred to the military court of Rabat.

On the 19th of July, Sbaai was condemned to life imprisonment by the Court of Appeal in Salé. Sbaai was condemned for the forming of a criminal organization and murdering a public officials in their line of duty, with the intent to kill. The main piece of evidence proving the act committed by Sbaai is the police records; confessions signed under torture, that Sbaai himself urges is falsified against him. Sbaai declared in the Court of Appeal that the Gdeim Izik camp was dismantled by the military forces, and that the clashes that occurred was a consequence of the violent dismantlement of the peaceful protest camp, that consisted of women, children and elderly.

Checikh Banga

Born: 1989

Sentenced to 30 years by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Cheikh Lkouri Bouzid Banga was born and raised in Assa, south of Morocco – home to a large Saharawi population that fled to the north when Morocco invaded Western Sahara. Cheikh grew up in a warm family, with his 2 brothers and 5 sisters.

Having a mind for books, Cheikh did well at school, but had to drop out due to repeated incarcerations. The Moroccan authorities prohibited him from continuing his studies after his release from prison. In spite thereof, he’s pursuing his bachelor degree in law from behind bars. Ever the avid reader, he’s particularly fond of the work of Noam Chomsky.

Cheikh is the youngest Saharawi prisoner of conscience. He’s been arrested many times for his advocacy for the Saharawi’s right to self-determination. He’s a member of CODESA, President of the Saharawi Committee for Human Rights in Assa and a member of Assa’s local chapter of AMDH (Moroccan Association for Human Rights). At the age of 17, in 2006, he spent 5 months in Anzigane jail. Barely released, he was arrested again in El Aaiún in October 2006 and sentenced to 6 months.

He was arrested on 8 November 2010 on the Gdeim Izik camp site. He had only just arrived on the scene bringing medicine for his aunt, who had pitched her tent in the protest camp. Cheikh was tortured by the Moroccan police and forced to sign a confession he had not been able to read in advance.

Banga was condemned to 30 years in prison by the Court of Appeal in Salé and found guilty of participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill. The main piece of evidence proving the act committed by Banga is the police records (confessions), that Banga himself declare are falsified and signed under torture. Banga declared during the proceedings held in the Court of Appeal in Salé that the Moroccan public forces attacked the inhabitants of the camp whilst they were sleeping, and that he had been assaulted and abducted in his tent on 8 November.

El Bachir Khadda

Born: 1986

Sentenced to 20 years by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017

Bachir Elaabed Elmhtar El Khadda was born on 26 October 1986 in a Saharawi family living in Tan Tan, a town in the south of Morocco, close to the Western Sahara border. He went on to live in El Aaiún, the capital of Western Sahara.

Bachir is a member of the Saharawi Observatory for Human Rights in Western Sahara. When he was 21, he was arrested and thrown in prison to serve a ten-month prison sentence for having participated in a Saharawi pro-independence demonstration. He finished his A-levels while in prison.

On 5 December 2010, Bachir was arrested in café Las Dunas in El Aaiún, where he was enjoying tea with Hassan Dah and Mohamed Tahlil. All three men were taken to the police station. Khadda says not to have been tortured, but says he was blindfolded and handcuffed throughout his detention.

Khadda was condemned to 20 years in prison by the Court of Appeal in Salé, and found guilty of participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill. Khadda declared that he was not present in the camp on the morning of the 8th of November, and urged that he did not commit the crimes accused of; and that the police records used as evidence against him was falsified and signed under torture. During his declarations to the Appeal Court of Salé, Khadda invoked the fourth Geneva Convention, and declared that a Moroccan courthouse had no competence to judge him. The main piece of evidence proving and describing the acts committed by Khadda is the said police records. Bachir is currently studying to obtain a law degree from behind bars.

Mohamed Tahlil

Born: 1981

Sentenced to 20 years by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Mohamed Tahlil was born in 1981 in Guelta Zemour, Western Sahara. He is currently registered as an inhabitant of Boujdour, where he lives alone.

Tahlil is the president of the Boujdour section of ASVDH – the Saharawi Association of Victims of Grave Human Rights Violations Committed by the Moroccan State. He’s been imprisoned for his political stance in 2005 and 2007. On both occasions, he’d been sentenced to three years in jail, but released after a year and a half. Tahlil is the president of the Boujdour section of ASVDH – the Saharawi Association of Victims of Grave Human Rights Violations Committed by the Moroccan State.

Tahlil was arrested together with Bachir El Khadda and Hassan Dah on 5 December 2010, while they were having tea in café Las Dunas in El Aaiún. Tahili says that he has not been subjected to torture, but did experience psychological abuse during his interrogation when he was blindfolded and handcuffed.

Tahlil was sentenced to 20 years by the Court of Appeal in Salé, and found guilty of participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill. Thalil declared himself innocent of all charges, and denounced that the only reason for his imprisonment was his political opinions. Thalil urged that he was not present in the camp during the early hours on the 8th of November. The only piece of evidence proving that Thalil was present in the camp during the early hours in the 8th of November is the police records which all accused urge are falsified and signed under torture.

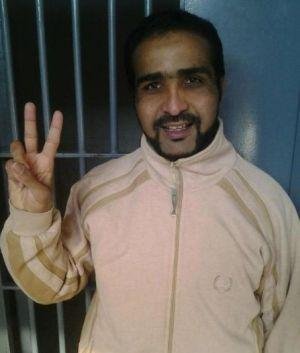

Hassan Eddah (Dah)

Born 1987

Sentenced to 25 years (originally sentenced to 30 years by Military Court in 2013, reduced to 25 years in 2017 2017 by the Appeal Court)

Hassan Dah was born on 18 January 1987 in El Aaiún, where he grew up in the Maatala neighbourhood – home to many Saharawis who still live in the occupied capital of Western Sahara.

Hassan is a human rights defender and connected to the Saharawi Observatory for Human Rights in Western Sahara. In 2007, he spent 10 months in prison for his political views. He finished his A-levels behind bars.

The Moroccan police arrested Hassan Dah, Mohamed Tahlil and Bachir El Khadda on 5 December 2010 in café Las Dunas in El Aaiún. Hassan says he’s been physically and psychologically tortured, kept blindfolded and handcuffed, has been raped with a baton, has had cold water and urine poured on him, in addition to various other human rights violations.

Hassan Dah took part in the Gdeim Izik camp, where he acted as a correspondent for the Frente Polisario’s TV and radio service – something the Moroccan court held against him when charging him with undermining state security.

The Appeal Court of Salé condemned Hassan Dah to 25 years in prison on the 19th of July in a blatant absence of material evidence. Hassan was found guilty of participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill

Hassan described to the court how he on the 7th of November had witnessed a caravan, bringing food and medicine in to the camp, being stopped by the military forces. Hassan described that the had observed the assault on the caravan as a human rights activist, and described how the camp was placed under a siege on the 7th of November, and that the military forces prevented people from leaving and entering the camp. Hassan declared that he was in El Aaiún on the 8th of November, and he declared himself innocent of all charges; declaring that the only reason for his imprisonment was his political beliefs that the people of Western Sahara is entitled to a referendum on self-determination. The main piece of evidence proving that Hassan Dah was in the camp in the 8th of November when the camp was violently dismantled by the Moroccan military forces are police records that Hassan himself declare are falsified against him and signed under torture.

Mohamed Lamin Haddi

Born: 1980

Sentenced to 25 years by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Mohamed Lamin Haddi was born in 1984 in El Aaiún, Western Sahara.

He was arrested by Moroccan secret service on 20 November 2010 in El Aaiún. He claims not to have been tortured, though he says he was subjected to human rights violations while being blindfolded, handcuffed and deprived from food.

It is believed that his arrest was linked to the assistance he had offered to two Belgian doctors, Marie-Jeanne Wuidat and Ann Collier, who were on a humanitarian mission in the occupied territories to provide medical assistance to Saharawi victims of Morocco’s repression in the Gdeim Izik camp. In the aftermath of the camp’s dismantlement, many Saharawi were refused help by the Moroccan staff in the hospital of El Aaiún. The Belgian doctors were expelled from El Aaiún.

Mohammed Lamin Haddi declared in the Court of Appeal in Salé that he was in El Aauin on the 8th of November, and witnessed the protests that emerged after the violent dismantlement of the camp. Haddi declared that he witnesses civilians being beaten in the streets, women being raped, and witnessed the military forces assault people in the streets. Haddi declared that two of his friends died that day.

Haddi was sentenced to 25 years by the Court of Appeal, and found guilty of participation to murder of public officials in their line of duty, with intent to kill. Haddi urged that the only reason for his imprisonment was his human rights activism, and urged that he was innocent of all charges. The only piece of evidence proving or describing the alleged acts committed by Haddi, or even his presence in the camp, are police records that Haddi urges are falsified against him and signed under torture.

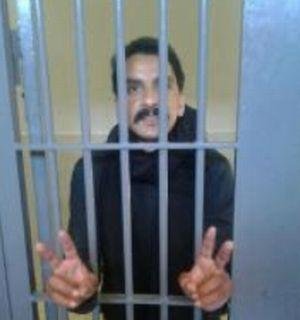

Abdallahi Lakfawni

Born: 1974

Sentenced to life by the Appeal Court in Salé in 2017.

Abdallahi Lakfawni was born in El Aaiún, Western Sahara, in 1974.

Abdallahi took part in the Gdeim Izik camp and contributed to keep the camp as organised as possible. On 5 November 2010, the wali (governor) of El Aaiún wanted to enter the camp, but was turned back by Lakfawni – an incident which is said to have been the main reason behind his arrest and conviction.

Abdallahi arrested on 12 November 2010 at Playa de Foum El Oued, 25 kilometres southwest of El Aaiún.

Abdallahi Lakfawni claims to have been subjected to different types of torture which lead to loss of consciousness during his detention; he was forced to undress, raped with a baton, burnt with cigarettes on his body, subjected to fake strangulation, ‘the plane’ and ‘grilled chicken’, and urine was poured over his body. Abdallahi was blindfolded while this horrific maltreatment was ongoing, and says to have been deprived of sleep and food.

Lakfawni was sentenced to life imprisonment by the Court of Appeal in Salé, in the absence of criminal evidence. Lakfawni was found guilty of the forming of a criminal organization, and guilty of the murder of public officials with the intent to kill. Lakfawni declared that he was present in the camp during the dismantlement, and explained how the Gdeim Izik camp was controlled with an “iron hand”, and how the camp was surrounded by military personnel, surrounded by a wall, with only one entrance. The military had made 7 checkpoints for us to enter the camp, Lakfawni declared. He told how he was asleep when the military forces attacked the camp, and that it was like an earthquake – it was chaos – people were running, and they screamed. He told how women and children passed out due to the teargas. Everyone walked back to the city. He stated: “If Morocco had wanted us to know the truth, we would have had the truth; but they have buried it”.

Lakfawni declared himself innocent of all charges, and urged that the police records, the main piece of evidence proving the actions of Lakfawni, was falsified against him and signed under torture.

Abdallahi Toubali

Born: 1980

Originally sentenced to 25 years by Military Court in 2013, reduced to 20 years in 2017.

Abdallahi Toubali was born on 24 March 1980 in El Aaiún – the capital city of occupied Western Sahara.

Abdallahi took part in the Gdeim Izik camp, and was a member of the Dialogue Committee, which attempted to negotiate with the Moroccan authorities to assure more respect for the social and economic grievances of the camp’s residents.

Abdallahi was run over by a police SUV on 7 November 2010 – the eve of the camp’s dismantlement. He was taken to the hospital of El Aaiún, but was refused medical assistance. Thanks to an intervention by Gachmoula Mint Ubbi – a Saharawi defector who has been elected into the Moroccan parliament – Abdallahi was taken in for first care in the military hospital. He was allowed to go home on 2 am of 8 November 2010. At 9 am, Gachmoula came by to visit him.